Book Summary- Alexander the Great (Part 3)

Welcome to the third of four articles summarizing Philip Freeman’s Alexander the Great. In the last article, Alexander invaded Asia, forcing Darius to retreat; conquered the Near East along the Mediterranean coast; and became the pharaoh of mighty Egypt. Hearing from the Sahara Desert’s legendary Oracle that he was son of Zeus and destined to conquer the world, he had a new sense of confidence. After founding the infamous Alexandria, Egypt, Alexander was ready to invade the Persian Empire, which had been dominating the intersection of 3 continents for the past 200 years.

Upon crossing the Sinai back into Asia, Alexander learned that the Samaritans (an offshoot of the Israelites) had burned alive Andromachus, the satrap Alexander had appointed to Samaria. Alexander pursued the Samaritans into the mountains where they hid deep in a dark cave. His soldiers followed them into the cave by torch light, killing them all. Their remains were found in 1962 along with some papyrus documents and other artefacts. This site is known as the Wadi_Daliyeh.

After handling some administrative work in Tyre, such as appointing Amphoterus to quell the full-blown revolt that the Spartans were leading in the Peloponnese and Crete, it was now time to head to Babylon to challenge the Great King. Alexander arrived at Thapsacus on the Euphrates River that August. From there, the Great King suspected Alexander would go south along the river, so he burned all the crops along the route to Babylon. To Darius’ surprise, Alexander decided to head northeast to the mountains of Armenia and then head south along the Tigris River instead.

The Macedonian army crossed the Tigris on September 20 331 BC, during the night of a blood-red lunar eclipse. Knowing that perhaps the largest battle in history would be any day now, many of the men began freaking out that the eclipse was an omen, however Alexander’s seer Aristander calmed them by stating it meant it was time for the Persian Empire to be eclipsed by a new one.

Four days after crossing the Tigris and marching south, scouts finally spotted a small band of Persian cavalry. Alexander sent a band of Paeonians to pursue them. Under the command of Ariston, the Paeonians killed many Persians, including their leader Satropates. The Paeonians would be very proud of this for generations to come, even minting a coin with the image of Ariston striking down Satropates. From the prisoners they captured, they learned that Darius was close by, waiting in the eastern plains of Gaugamela. He had been there for several days smoothing out hills and dips to make the battlefield as smooth as possible for his cavalry and war chariots and had carefully planted hidden stakes and ditches.

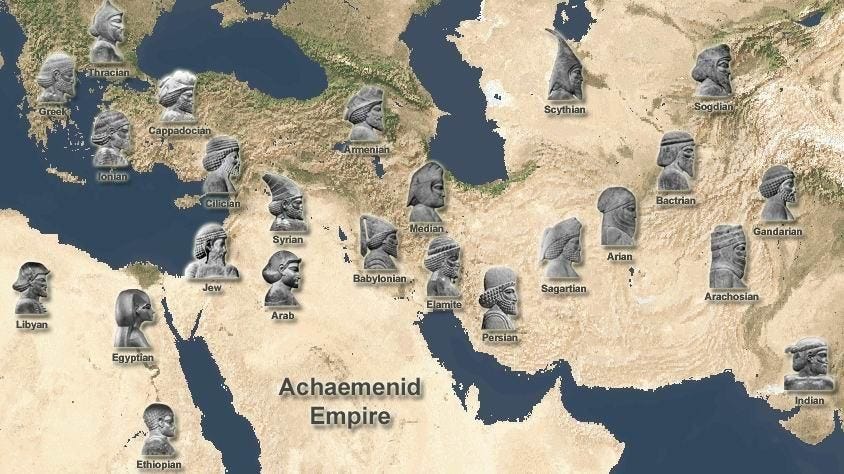

Darius had learned from the Battle of Issus that it was very important not to be caught in a narrow plain (so his numbers could be better utilized). Alexander had about 50,000 soldiers, while Darius had at least twice that. Darius had gathered elite soldiers from the four corners of his realm. This included Indians from Hhyber Pass (who brought war elephants, which the Mediterranean world had never seen in battle), mounted archers from Scythia, and countless other warriors from Bactria, Sogdiana, Arachosia, Parthia, the Hyrcani, the Medes, Cadusians, Sacesinians, the Albani, Armenians, Syrians, Cappadocians, and Greek mercenaries from Asia Minor. He of course also had the support of his local Babylonians and the Arab horseman of the Arabian Peninsula.

Alexander reached the edge of the hills, peering down onto the plains to witness Darius’ vast army. Alexander was in an advantageous position (on the hill) and knew it was he who decided when the battle would begin. He decided to give his men plenty of time to rest and prepare themselves psychologically, while his opponents would only grow more anxious awaiting the Macedonian attack.

There is great detail available on the Battle of Gaugamela, but basically, Alexander did his usual tactic that he and his father had perfected. This involves attacking the enemy’s flank, causing them to maneuver their center to provide their flank support, which ultimately exposes the center and allows the Macedonian army to break through. This tactic worked yet again, and now Alexander and his cavalry had ripped through the center and were charging at Darius and his royal guards. Alexander was riding Bucephalus, who by now was past his prime, but Alexander wanted no other steed on this glorious day. Darius had begun to retreat, but as Alexander pursued him, he realized the Persian cavalry had broken through his own center. He could pursue and kill Darius but it would mean leaving his army behind to be slaughtered by the Persian cavalry. Alexander decided to circle back to rescue his men and save Darius for another day.

Darius retreated deep into the Median region of his empire, near the city of Ectabana, remaining elusive and engaging in guerilla warfare. Alexander decided to secure the center of the Persian Empire before pursuing Darius in the east. The Macedonians continued south through modern day Iraq to the great city of Babylon. Along their journey they’d pass fields with bitumen (oil) bubbling up from the ground. One local leader even put on a show, making a trail of oil to Alexander’s tent and lighting the flame for it to race along the pathway, illuminating the way for Alexander.

Rather than sack Babylon, Alexander negotiated with the local satrap Mazeus (who had just fought against him at Gaugamela). It was very important for Alexander to maintain local leaders who knew how to rule these regions of the empire unknown to the Macedonians, and it would serve as a pivotal moment for Darius’ key regents to now pay tribute to Alexander.

Back home, news of Alexander’s victory was not well received by certain Greek city-states. King Agis of Sparta would lead a revolt, only to be met by Antipater’s forces and die on the battlefield, putting an end to the rebellions at home.

Babylon

Herodotus claimed the Babylon was founded by Queen Semiramis, who built a massive dyke to prevent Mesopotamia from flooding. He claimed the city was shaped like a square, 13 miles on each side, with a large moat surrounding the walls. The walls were 75 feet thick and 300 feet high, and the entire perimeter had a path on top in which a 4-horse chariot could ride around. The Euphrates divided the city in half, but there was a bridge that connected the two sides. There were many gates into the city, with the grandest being the Ishtar Gate. The city had grid-like streets, with buildings 3-4 stories high serving as houses and shops containing goods from all over the world. On the eastern side of the city was another wall surrounding the palace and the temple of Bel-Marduk. Alexander and his men had never seen a city like Babylon before. Here they found the hanging gardens, one of the 7 wonders of the ancient world.

A section of Babylon belonged to the Chaldeans. “Mathematics as taught by the Chaldeans was based on the number sixty rather than ten- a way of measuring time and space passed on to later civilizations as the sixty-minute hour, the 60-second minute, and the 360-degree circle. Long before Alexander, the Babylonians had discovered how to use complex fractions, quadratic equations, and what would come to be known as the Pythagorean theorem. Many advances in later Greek mathematics in fact derived from the encounter that began in Babylon that autumn with the arrival of the Macedonians.”

After a month of rest at Babylon, Alexander rallied his troops to go secure the treasures of Susa and Persepolis while Darius was still at large. Susa was the old capital of the ancient kingdom of Elam, whose language was used throughout Persia. It took 20 days to march about 100 miles to Susa. The Great King’s palaces at Elam were very extravagant—the local word to describe the palace, paradayadam, became the word for paradise. The treasury at Susa contained 40,000 talents of gold and silver as well as thousands of minted gold coins. The treasury contained enough riches for Alexander to fund his army for years. Alexander left Darius’ family at their home in Susa (who had been with him since the battle of Granicus). Alexander was now heading into official Persian territory, where he would no longer be perceived as liberator, but as invader.

Persepolis

From Susa, the Macedonian army entered the snow-covered mountains of the Uxians on their way to the Persian capital, Persepolis. For hundreds of years, the Uxians let travelers through the narrow pass, as long as they paid a fare. Even the Great King and his army would make the payment, but Alexander refused. Instead, he launched a campaign of terror, raiding their villages at night until they finally submitted. In the end, they were made to pay Alexander 100 horses, 500 transport animals, and 30,000 sheep every year.

The Persian Gates was a very high and narrow pass through the Zagros mountains and was the way to Persepolis. Alexander knew that the Persian general, Ariobarzanes, had a considerable force waiting for him there. There was also a much longer route that went around the mountains. Alexander decided to split up his army and go both ways, sending Parmenion the long way.

As Alexander led his men up the pass, right as they were at the steepest part, 40,000 of Ariobarzanes men began bombarding them from above with rocks, arrows, and catapults. Alexander’s men tried making a tortoise shell with their shields, but hundreds were getting knocked down the mountain to their death. Alexander had to retreat and leave the corpses of hundreds of his best men. The Macedonians managed to capture a few enemy soldiers, among them being an exiled Greek from Lycia. The Greek had been a shepherd before he was drafted into the Persian army and told Alexander of a mountain pass suitable for a flock of sheep, but only during summer months. Alexander recalled an oracle’s message from when he was a boy, that he would be led into Persia by a wolf. The Greek word for wolf was lykos, similar to Lykios (Lycian). Alexander insisted that the man take half his men through the pass, despite it not being the proper season. They passed through a steep, trailless part of the mountain on a freezing night, sometimes trekking through waist-deep snow, with some men falling into hidden ravines. Eventually, they made it around the Persian Gates and behind Ariobarzanes. Alexander attacked from both sides, crushing the enemy and paving the way to Persepolis.

As Alexander’s army descended from the mountains, they passed a community of 800 disfigured Greeks. A limb, nose, or ear and been removed as punishment from Persian Kings. Alexander offered to send them all home, but they would rather stay there in their community instead of return home and be the local freak. Alexander gave them enough money to live comfortably until the end of their days and ordered for them to be treated with great respect.

In January, four years after entering Asia, Alexander reached Persepolis, the heart of the Persian Empire. At the city gates, Tiridates, Persepolis’ treasurer, met them with the keys to the treasury. The Great King’s palace was truly spectacular, as it had been where all of the spoils of Persian conquests had accumulated over the past 200 years. Each King had their own palace constructed in a massive complex and included a large audience hall. Darius’ palace walls were polished so well that it was known as the Hall of Mirrors. There were many rooms for the King’s wives and concubines, guarded by eunuchs, as Persian Kings had to be completely sure that their child was their offspring. The Persian elite lived outside the palace in the city of Persepolis.

As Alexander’s army entered the city, they exercised great restraint passing all the riches. There was great tension in the air as after marching against Darius for four years, they were expecting to pillage and claim their spoils of war. Alexander eventually caved in, allowing for the first time a surrendering city to be pillaged (with the exception of the royal palace). That night, the army went absolutely ape-shit on the Persians. Amidst the death and destruction, Alexander finally sat upon Darius’ throne. This moment marked the climax of his ambitions. There was so much gold in the treasury that Alexander had to send for thousands of mules to carry it all.

The next day, Alexander went to nearby Pasargadae. Here stood the tomb of Cyrus, founder of the Persian Empire. His tomb was a very modest structure, nowhere near as grand as the tombs of the other Persian Kings. The inscription above his tomb read, “Mortal Man, I am Cyrus, Son of Cambyses, Founder of the Persian Empire and King of Asia. Do not Begrudge Me this Small Monument.” It was as if Cyrus was asking Alexander not to desecrate his tomb. Alexander honored the request and ordered his men to treat it with respect.

At this point, Alexander had achieved his main objective and it wasn’t exactly clear what to do next. Darius and the remnants of his army were in Media, but Alexander was in no rush to fight them. His men wanted to rest and party for a bit in Persepolis. Alexander still sought adventure however, and decided to spend the rest of the winter wandering deep into the wilderness of the Zagros mountains with 1,000 of his men. There was no real objective, Alexander was probably just having a mid-life crisis. There they hunted the very isolated, cave-dwelling Mardis people pretty much for sport. When Alexander returned to Persepolis, he burned former Persian King Xerxes’ palace to the ground.

Pursuit of Darius

Darius was 400 miles north, in the Median capital of Ecbatana. He had with him about 10,000 men and was waiting to see what Alexander would do. His plan was to flee east across the mountains into Bactria. The land there was already rather barren and he would burn the crops as he went, making it very difficult for Alexander’s army to pursue them. Alexander knew this was Darius’ intention, but he also knew that he would not be recognized as King of Persia until Darius was dead. Alexander explained the war would end when the shah, Persian word for King, was mat, finished. The Persian phrase which evolved into the word checkmate.

As winter neared an end, Alexander decided to march to Ecbatana at lightning speed and get to the Great King before he could flee. His men marched there at a rate of 20 miles a day. When they were three days away from the city, the Persian noble Bisthanes arrived at Alexander’s camp. He informed him that Darius had fled and was on his way to the Caspian Gates.

In that moment, Alexander told the Thracian cavalry, which had been a major force in his army since the beginning, that they were free to go home. Parmenion had been a major leader of the army over the years, and letting these men go home gutted the remaining backbone of Parmenion’s power, as Alexander had also been assigning men loyal to him to various cities over the years. Alexander then assigned Parmenion to watch over the treasury of Ectabana, pretty much saying he didn’t need the 70-year-old anymore and assigning him to guard duty.

Alexander raced so fast to the Caspian Gates that several men were left behind and horses were being run to death. When Alexander reached the pass, Darius was only a few days ahead of him. As Alexander’s men camped, they were informed by deserters who had just left Darius’ camp that there had been a coup and that Darius had been taken prisoner by Bessus, satrap of Bactria. Alexander didn’t want a Bactrian to declare himself King and potentially gather support from all of Bactria, so he immediately left to pursue the imprisoned King, even leaving behind men who were hunting and gathering supplies. Alexander raced frantically to catch up, lightening his load more and more and even travelling at night.

Finally, when Bessus realized Alexander was on his heels, he stabbed Darius and left him for dead. A Macedonian soldier namely Polystratus, while fetching water, came across a dying Darius. The dying king motioned for water, which the soldier gave him from his own helmet. Darius died right there in the attendance of a single Macedonian soldier.